At the Polo Grounds in New York City 88 years ago today, a Notre Dame backfield of four seniors who had played together — and defeated all but one opponent — since their sophomore year, went up against another great Army team. It was the sports event of the year on the East Coast, with hoopla and fan interest aplenty. We look back at one of the seminal days in ND football history.

Saturday, October 18, 1924, dawned sunny and pleasant in New York City. The Irish bused into the city from Rye for Mass followed by breakfast at the Belmont Hotel. Conversation was minimal. The task was at hand. By late morning, the subway lines came alive with the bustling activity generated with the arrival of college football fans. They carried pennants, lunch boxes, and jackets. Throngs arrived from a distance and appeared as columns of determined ants converging on the great stadium from several directions. The ticket booths were jammed by customers who hadn’t availed themselves of the advance sale.

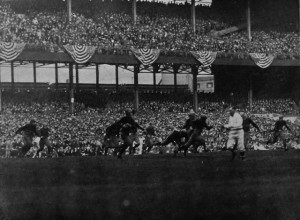

Spread below was the green grass and green grandstands of the Polo Grounds. It was almost as though the Emerald Isle was smiling on the Irish. But the crowd would be composed of a variety of people. Some, like the Irish-Americans eager to see Notre Dame, were true partisans. Others were drawn by the prospect of seeing two powerful gridiron elevens match wits, strategy and strength. And still others looked forward to the great spectacle and pageantry of the day. The Polo Grounds sported a patriotic theme, with red, white and blue bunting decorating the façade of the upper deck left over from World Series.

At ten minutes after two, as many in the huge crowd were settling into their seats, the ceremony began. From deep in center field at the east, or “open” end of the horseshoe, the huge gate slowly opened. To the roar of the crowd, in marched the West Point Band. They played grand marches as they led the corps of cadets onto the field. Column after column of gray-clad cadets entered the stadium, and they made an immediate right flank and continued to march along the north stands. The “long gray line” marched with crisp precision, their arms swinging in seemingly-effortless unison. Toward the west end they spread and then turned and paraded along the end zone behind the goal posts. Another “left flank, march” and they continued to their destination, at the midpoint of the south grandstand. All along the route, the 1,200 cadets were greeted by loud, sustained cheering.

After the cadets took their places in the seats, forming a solid block of gray in the midst of the grandstand, their star performer arrived. Bessie the mule was led onto the field and greeted with a riotous welcome by the corps. She was bedecked in a gray blanket with gold piping and a large “A” framed by stars.

By now, Coach McEwan had led his troops onto the field for a brief warm-up, then back into the dressing room for final plans. Rockne’s squad hit the field with full force, with three full elevens breaking off a series of dummy plays in perfect formation. Every ten yards, the men would set themselves, await the signal, then erupt in motion for another “first down.” The crowd, which now filled the place to capacity, loved the show.

At zero hour, two-thirty, referee Ed Thorp blew his whistle and called the captains together at midfield. Adam Walsh, right hand in a cast, greeted Ed Garbisch with a left-handed handshake. The two warriors had great respect for each other.

Notre Dame won the coin toss and elected to kick off. A great roar reverberated through the horseshoe as Stuhldreher drove his foot into the ball from midfield. Army’s Gillmore, showing the expected nervousness in this setting, took the kick at the 15 and momentarily fumbled it before regaining possession. A minute later, Stuhldreher would do the same thing, in fielding the first of Wood’s punts.

Both teams started cautiously, like a great pair of heavyweights parrying and thrusting, seeking the opponent’s strategy. Depending on field position, they might run only one play from scrimmage before punting, in the hopes of pinning the opponent deep in its own end. Every play was a fierce skirmish; every yard was hard-won. On one of the first plays of the game, Walsh went to block Garbisch, but the wily cadet jumped like a rabbit to avoid the hit. When he came down, one foot landed squarely on Walsh’s left hand, Garbisch’s cleats carrying the weight of the 180-punder. Walsh felt a searing pain radiating from his hand. This can’t be happening, he thought to himself. The game meant everything to him and his fellow seniors. The pain wasn’t subsiding, but it had to be overcome. Somehow, he willed himself to continue.

The scoreless first quarter ended with Army facing fourth down. This time, Garbisch set up for a drop kick and got it away cleanly, but the ball sailed wide of the upright. Notre Dame took over at its 20. Aware they were fortunate to still be tied, the Irish gathered with a new resolve. Crowley took a reverse handoff from Miller, darted through an opening and broke free for 15 yards out to the 35. Layden followed Joe Bach’s interference and worked his way to the 41. It was Miller’s turn, and he dashed for 10 yards into Army territory. This was more like the South Bend attack that had flummoxed opponents the past three seasons. The shift, and its myriad of fakes and feints, along with cross-blocking in the line, in which Army’s linemen were never sure who would be coming at them, was creating confusion through the West Point defense.

Garbisch, as was his wont, would often drop out of the line and play a yard or two back, more as a rover to get to the ball. As the lines set, one of the Irish shouted, “Hey, Ed, we’re going right through the middle. Better get back where you belong.” Stuhldreher, the savvy signal-caller, mixed plays brilliantly, firing a pass to Crowley for another 12 yards. Crowley then rushed for another five through the line. On another reverse, Miller skirted left end and dashed 20 yards before being driven out of bounds at the Army 11. The Notre Dame rooters were frenzied as their heroes marched downfield. And the non-partisans in the huge crowd were getting a sense of just what this team, and backfield, could do.

Crowley adroitly picked the opening off of Rip Miller’s block, twisted through right tackle for eight yards down to the three. From there it was power football, with Layden smacking into the line once for a yard, then again for the game’s first touchdown. Stuhldreher missed the kick, but ND led, 6-0. The Irish machine kept rolling, with a dizzying array of plays befuddling the soldiers. They engineered another long drive which only ended when a pass by Miller was intercepted by Yeomans at the Army goal line. Yeomans had a clear line along the sideline and sprinted nearly 40 yards before Stuhldreher and Miller knocked him out of bounds to prevent a total turnaround.

The half ended with Notre Dame leading, 6-0, and with a huge measure of momentum on its side. In the second quarter, the Irish had eight first downs to none for Army. The Irish appeared as if they could march almost at will. The teams made their way to their dressing rooms. A quick examination of Walsh’s battered left hand showed that it, too, had broken bones. Two broken hands and yet no one – least of all Walsh – suggested he leave the lineup.

Up in the wooden press box, newspaper men were marveling at the precision and skill shown by Notre Dame in the second quarter. One group of sportswriters included some of the biggest names in the business. Grantland Rice of the New York Herald Tribune and syndicated column fame was holding court. Rice was considered the dean of newspaper sports writers, and his mere presence was enough to grant significance to any event. His syndicated newspaper accounts were circulated six days a week to more than 100 newspapers nationwide with an estimated audience of 10 million readers.

It was said by Rice’s peers that he was a “disciplined craftsman who turned out a prodigious amount of work.” In addition to writing for the Herald Tribune in ‘24, Rice was dazzling readers – and collecting royalties – by writing Sportlight, his syndicated columns, as well as authoring numerous books and writing for several magazines.

Behind Rice’s booming Southern voice and six-foot frame there was a depth of feeling and warmth that was often noticed by others. He was known as someone who listened as well as he talked – a person to whom others naturally gravitated. Such was the case this October Saturday at the Polo Grounds. With Rice in the press box at half time were: Damon Runyan, who had gained fame covering baseball and boxing for William Randolph Hearst’s New York American and was called by Hearst “the best reporter in the world;” Gene Fowler, serving as backup to Runyan; Jack Kofoed, who had started his newspaper career in Philadelphia as an 18-year-old in 1912 and was now with the New York Post; Paul Gallico of the Daily News, at 27 already one of the most powerful sportswriters in the city; Davis Walsh, lead football writer for the United Press and Notre Dame alum Frank Wallace, reporting for the Associated Press.

Into this conclave strolled young George Strickler, Rockne’s publicist and South Bend Tribune correspondent. Part of his assignment from Rockne was to keep an ear open for scuttlebutt and analysis from the “big guys” in the newspaper business. The conversation revolved around the exceptional work of the Notre Dame backfield in thwarting Army at every turn.

“Yeah, just like the Four Horsemen,” Strickler piped up, recalling Wednesday’s movie. No reaction was noted from among the professional scribes. The confab eventually broke up as folks settled into place for the second half.

Notre Dame, eager to continue its charge, hit the field first for the second half, followed a minute later by the Army. Layden stood on the goal line on the east end, awaiting the kickoff from Garbisch. The Irish fullback took the ball near the goal, and followed the formation out to the 20. After Crowley was dropped for a two-yard loss, Miller again came up big. Charging out of the backfield, he picked his spots, changed direction and evaded Army tacklers for 40 yards before Wilson finally wrestled him to the turf. The crowd let out a huge roar as the Irish machine again looked to be cooking.

Army’s Wilson intercepted an Irish pass, but Layden got the ball back a minute later with one of his own. It was a typical big play for the senior, and it lifted his teammates. Walsh, playing with excruciating pain, continued to have an impact on nearly every play.

On first down, Crowley feigned right, then ran left again and sprinted to the Army 35 before he was forced out of bounds. Rip Miller created an opening, and Don Miller obliged for another five yards. Layden followed Kizer’s block for another 10 to the Army 20. Again, the crowd was buzzing at the tremendous coordination and sophistication of the Irish attack. Notre Dame, lining up quickly, going into the shift and snapping off plays in rapid succession, seemed to be catching the Cadets flat on their feet.

After Miller lost a yard on first down, Crowley’s number was called. He took off around right end behind a wedge of blockers – Miller, Layden, Stuhldreher, Kizer and Rip Miller. Crowley shot through an opening, shook off the grasp of a pair of Cadets, then stiff-armed another to break free. Racing the Army secondary, Crowley eyed the corner of the field. Striding full-tilt, he arrived ahead of a defender, made a last-second cut to avoid going out of bounds and barely sliced across the last foot of the goal line for a touchdown.

Army’s defenders were scattered about the field. Some had just missed making contact with Sleepy Jim, some had him but lost their grip, others could only watch his flying cleats as they gave chase. The turf on the west end of the field, laid to cover the baseball infield, was new and caused some slips. But Army couldn’t blame the field; they had been bettered by an attack that hit on all cylinders. Crowley kicked the extra point for a 13-0 ND lead, a margin that held through the third quarter.

Early in the fourth quarter, with Army facing a fourth down and five from the ND 15, the snap went to Harding, who faked a handoff to Wood and pulled away with the ball. Wood dove into the right side of the line, while Harding circled left end and raced untouched to the end zone, sending the Army rooters into a frenzy. Garbisch drop-kicked the point, and Army was back in it, trailing 13-7 with 10 minutes left. He then went from teammate to teammate, encouraging them to keep fighting because victory was within sight.

Garbisch kicked off to the Irish 13, and three plays later Layden punted the ball back to Garbisch, who was downed on the Army 46. The Army, looking spent, couldn’t mount a drive. After each play, Adam Walsh dragged himself to his feet, took his position, called the defensive signal and, more often than not, made the next tackle.A series of punts left Army at its own 35 with the ball and time winding down. Tom Trapnell went in at quarterback for the Army, now desperate to get the ball downfield. Surely a pass would be coming. In a surprise move, though, it was Wilson who would launch it. He had a bead on a receiver, but Adam Walsh leaped into the air and came down with the leather cradled in his smashed hands. The final serious Army threat was vanquished. After referee Thorp’s pistol signaled the end, two exhausted teams left the field to the appreciative cheers of fans who realized they had seen a battle of two giants. It was Notre Dame’s quick-striking precision and speed that dominated the second and third periods and knocked the Cadets back on their heels from where they could never fully recover.

Both captains, the centers, had given their all. Garbisch wanted to enter the Notre Dame locker room to congratulate Walsh, but Rockne intercepted him. Thanks for the thought, the coach told him, but Walsh was in no shape to see anyone but a doctor. Walsh was taken to Roosevelt Hospital on 10th Avenue where an X-ray showed two small broken bones in his left hand to go with the three he already had in his right hand. Doctors urged Walsh to remain in New York for treatment, but he insisted on returning home with his team.

Grantland Rice, in the evening twilight and gathering chill, sat at his typewriter in the Polo Grounds press box and pondered his opening. National readers of his Sportlight column were used to Rice’s poems, odes and flowery speech. He regularly made an effort to liven the mundane with a clever turn of the phrase. He was well-read in classical literature, having majored in Greek and Latin at Vanderbilt.

Something about Strickler’s halftime comment and the imagery of horses stuck in Rice’s mind when he reflected on the Notre Dame backfield. He recalled the 1923 game at Ebbets Field, which he took in from field level. At one point, he recalled, the charge of the players on an out-of-bounds play brought to mind the possibility of being trampled by a runaway team of horses. It all clicked. His fingers hit the typewriter keys:

Outlined against a blue-gray October sky, the Four Horsemen rode again. In dramatic lore they are known as Famine, Pestilence, Destruction and Death. These are only aliases. Their real names are Stuhldreher, Miller, Crowley and Layden. They formed the crest of the South Bend cyclone before which another fighting Army football team was swept over the precipice at the Polo Grounds yesterday afternoon as 55,000 spectators peered down on the bewildering panorama spread on the green plain below.

A cyclone can’t be snared. It may be surrounded, but somewhere it breaks through to keep on going. When the cyclone starts from South Bend, where the candle lights still gleam through the Indiana sycamores, those in the way must take to storm cellars at top speed. Yesterday the cyclone struck again, as Notre Dame beat the Army, 13 to 7, with a set of backfield stars that ripped and crashed through a strong Army defense with more speed and power than the warring cadets could meet.

From there, Rice described “the driving power of one of the greatest backfields that ever churned up the turf of any gridiron in any football age.” He noted the following on the second quarter scoring drives: “the unwavering power of the Western attack that hammered relentlessly and remorselessly without easing up for a second’s breath.” Rice paid particular homage to the speed of the Irish attack, the precision with which it worked, and the consistently effective blocking it used to advance the ball on the ground.

“Always in front of these offensive drives could be found the whirling form of Stuhldreher, taking the first man out of the play as cleanly as if he had used a hand grenade at close range,” Rice wrote. “This Notre Dame interference was a marvelous thing to look upon.”

He also had high praise for ND’s defensive play. “When a back such as Harry Wilson finds few chances to get started you can figure upon the defensive strength that is barricading the road. Wilson is one of the hardest backs in the game to suppress, but he found few chances yesterday to show his broken field ability. You can’t run through a broken field until you get there.”

He concluded by stating that “we doubt that any team in the country could have beaten Rockne’s array yesterday afternoon, East or West. It was a great football team brilliantly directed, a team of speed, power and team play. The Army has no cause for gloom over its showing. It played first class football against more speed than it could match. “Those who have tackled a cyclone can understand,” Rice ended.

Over the next several weeks, a publicity photo staged by Strickler using four borrowed work horses – and Notre Dame’s series of victories over Princeton, Georgia Tech, Wisconsin and Nebraska – would propel Rice’s words, and this Notre Dame team, into the stuff of legends.

The preceding is excerpted from Loyal Sons: The Story of The Four Horsemen and Notre Dame Football’s 1924 Champions, by Jim Lefebvre. Copyright 2008 Great Day Press.