Editor’s Note: The following is excerpted from the award-winning biography Coach For A Nation: The Life and Times of Knute Rockne.

As Notre Dame prepared to head to New York City to play Army at the Polo Grounds, football fans across the country grew eager with anticipation for the intersectional battle of the year. Under Rockne’s leadership, Notre Dame had moved past an intriguing interloper stealing the thunder from the more established names in the sport; it was becoming the standard against which all other teams were compared. Those doing the comparing included the nation’s most prominent writer of sports, Grantland Rice. At the New York Herald Tribune, Rice’s columns were a feature of the running New York newspaper wars. But his audience was truly national, as his syndicated column The Sportlight ran in more than 100 newspapers nationwide with an estimated audience of 10 million readers. Rice had also authored numerous books and written for many popular magazines, including Colliers, American Magazine, McClure’s, Outing, Literary Digest and Country Life, his poems, odes, and flowery speech entertaining readers. He made a consistent effort to liven his subjects with a clever turn of the phrase. The Tennessee native majored in Greek and Latin at Vanderbilt, where he also starred on the baseball team at shortstop, played football despite numerous injuries, and ran track.

He was also attracted to the glamour of the foot soldier after habitual reading of Rudyard Kipling, in which war was romanticized and shown as adventuresome. He enlisted for service in the Great War in December 1917. Private Rice displayed superior skill and talent and was quickly promoted to Second Lieutenant. He eventually saw duty in the European campaign, although he never learned how to load artillery; instead, he put his talents to work writing for Stars and Stripes, the eight-page weekly which reached a peak of 526,000 readers during the war. He also dabbled in poetry while in Europe, though he failed to dazzle critics.

In September 1924, Rice looked ahead with excitement to October 18, when in addition to the Notre Dame-Army game, Dartmouth would meet Yale and Michigan would travel to Illinois. He considered them three of the best games of the year. “We have an earnest desire to look upon all three contests, and yet so far have discovered no answer to the complication,” Rice wrote. He went on to note, “Rockne rarely leaves the east without his annual supply of scalps. But the odds are he will have a better Army team to overthrow than he has faced for some time. Wilson alone is half a team.” Rice may have had in interest in watching the other two games, but he would be at the Polo Grounds, as he had been at Ebbets Field the previous year to watch Notre Dame and Army. He attended that game with Brink Thorne, Yale’s outstanding 1895 captain. They had sideline passes only, and Rice recalled nearly being run over by the Irish backfield on one particular end run. “It’s worse than a cavalry charge,” Rice said to Brink as he scrambled back to his feet. “They’re like a wild horse stampede.”

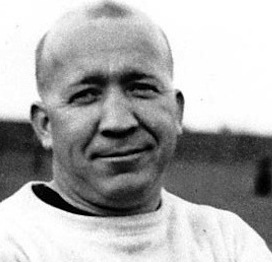

Rice first met Rockne when Notre Dame played at West Point in 1920. He went with fellow New York writer Ring Lardner, who grew up in Niles, Michigan, just miles from Notre Dame, and was aware of its budding football fame before most in the East. Rockne made an immediate and lasting impression, and the two became great friends. “Rockne was a man of great force, deep charm, and an amazing personality,” Rice would later write. “I have never known anyone quite his equal in this respect…Whenever there was a gathering of coaches in any city, there was usually just one question. ‘Where’s Rock staying?’ That’s where they all gathered. There have been so many fine coaches, but Rockne was the greatest of all in the way of human appeal.”

Rice thought back to one of Rockne’s earliest trips to the city. Rice suggested the pair attend a late-afternoon cocktail party hosted by Vincent Bendix, an automotive and aviation inventor and industrialist, at Bendix’s midtown apartment. Rockne was hesitant, but Rice assured Rockne that seeing magician Nate Leipsic, who was providing the afternoon’s entertainment, was worth the trip. Rice was correct; the magician’s skill astonished Rockne. Leipsic made rubber balls “disappear.” He showed again and again how much faster the hand is than the eye. Rockne asked to see some tricks repeated. He came away inspired. “I’ve learned a lot today about deception in handling a ball,” Rockne told Rice. “This matter of handling and facing with the ball is one of the biggest things in football, and I aim to make it bigger.” From that point on, his Notre Dame quarterbacks were excellent at faking with the ball. None was better than his current signal-caller, little Harry Stuhldreher. In 1923, Rice invited Rockne to his apartment for a Sunday brunch the morning after the Ebbets Field game. Rockne brought Stuhldreher, and Rice and his wife Kit marveled at this seemingly miniature football genius, whom they called “Rockne’s brain” on the field. It was the beginning of an enduring friendship between Rice and Stuhldreher.

In New York, Rockne’s old pal and Notre Dame alum Joe Byrne, Jr. had worked hard promoting the 1924 Army game and selling tickets for it, and a large crowd was expected at the Polo Grounds. New Yorkers of all stripes were lining up to see Rockne’s “wonder team.” And across the country, those who followed sports—especially readers of Grantland Rice—wondered whether Rockne would again prevail against the Army. The Notre Dame following extended far beyond alumni now scattered about the country. Catholics nationwide had a unifying representative in the Fighting Irish. First- and second-generation immigrants saw themselves embodied in some of Notre Dame’s players—and certainly in Rockne. These fans brought another wave of support.

There were still others—school and college coaches who had learned from and met Rockne at coaching schools in Springfield, Massachusetts; Williamsburg, Virginia; Corvallis, Oregon; and Notre Dame, Indiana—who could point to Rice’ s columns and other coverage of Notre Dame and say with pride, “I know Rockne! I’ve met him and talked with him, and consider him my friend.” By extension, the young men playing football for these coaches quickly turned into followers and fans of the team from northern Indiana.

The travel to New York meant a short week of practice, so Rockne called for a Monday marathon session to prepare. Rice was correct to highlight Harry Wilson’s strength. The flashy back from Penn State was representative of one huge advantage West Point had over all other teams: the ability to enroll superlative football players who had completed their normal athletic eligibility at their original school. Another backfield star was Tiny Hewitt, formerly of Pitt. Centering the line was the most veteran player on this or any other college football squad, 24-year-old Ed Garbisch, the captain of the corps of cadets as well as the football team. A product of Washington, Pennsylvania, he played four years for his hometown university, Washington & Jefferson, from 1917 through 1920. He was now in his fourth and final year playing for Army, his eighth campaign overall. This would be his fifth time facing Notre Dame, the first being Notre Dame’s 3-0 victory over Washington & Jefferson in 1917, in Jesse Harper’s final game as coach. Going up against Garbisch would be a challenge for an opposing center on any day. Adam Walsh would carry a handicap with him into this game, as he had suffered a broken bone in his right hand during the Wabash game. Stuhldreher was fine, but Walsh’s injury, which Rockne had carefully kept hidden, was sure to be a major hindrance.

Wednesday evening, the day before the squad headed for New York, several of the players walked from their halls to Washington Hall, where Notre Dame Brother Cyprian would occasionally show second-run movies. The bill this evening featured The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse, a drama starring Rudolph Valentino. The film was based on the novel of the same name, written by Vicente Blasco Ibanez, and it propelled Valentino to stardom. Valentino played Julio, the hero of a story based on greed, self-indulgence, love, and war set in Argentina and France before the Great War. In the movie’s climactic scene, Julio encounters a prophet known as the “stranger” who foresees the end of the world and calls out the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse from the Book of Revelation. They charge out of the clouds on horseback: the helmeted Conquest, the hideous War, then Pestilence, and finally Death. Among those watching Wednesday night’s showing was George Strickler, Rockne’s young publicist and student newspaper writer who had become a great fan of the movie.

Thursday, October 16 a squad of 33 Notre Dame players, along with their coaches, manager Leo Sutliffe, and cheer leader Eddie Luther boarded a train at South Bend’s New York Central station. After years of preparing for this moment—as a player, as an assistant coach, as a head coach facing the challenges of a war-shortened season, a star that went his own way, and players stealing away to pro games—everything was finally in place. Rockne described Stuhldreher, Crowley, Miller, and Layden as “four young men so eminently qualified by temperament, physique, and instinctive pacing to complement one another perfectly and thus produce the best coordinated and most picturesque backfield in the recent history of football.”

For Notre Dame students, Saturday began as usual, with classes until noon. An hour before game time, the entire student body would pack the dirt-floored Fieldhouse, just east of Washington Hall. They would come to “view” the game on the grid-graph, an innovation first used for major away games in 1922, provided by the Student Activities Committee. A large rectangular glass-like screen was marked off with the lines of a football field. A student would hold a flashlight behind the screen to indicate the progress of the ball. Student runners would receive updates on the game at the Western Union telegraph office, on the ground floor of the Main Building, and race what seemed to be the length of a football field to the Fieldhouse and give the details to the “light man.” The university band would play before the game and during breaks, and the atmosphere was lively and loud. Admission was 25 cents. Across town, the Palais Royale was also charging 25 cents admission for its grid-graph showing of the game.

The train carrying Notre Dame pulled into the New York Central station about mid-morning Friday, and the team had breakfast at the Belmont Hotel before being ferried by automobiles through the Bronx and up the Boston Post Road to their headquarters at the Westchester-Biltmore Hotel at Rye, New York. The pastoral setting was to Rockne’s liking since it lacked the noise and distractions of the big city. New York was bustling with activity, in which monumental achievements were nearly routine. Earlier in the week, officials of the “Highway under the Hudson” announced a major milestone in building a tunnel expected to double the amount of traffic carried between New York and New Jersey. At Grand Central Palace at Lexington Avenue and 46th street, the New York Edison Company was sponsoring the Electrical and Industrial Exposition, where electric trucks, electric elevators, electric refrigerators, and “a wide variety of household applications” would be on display. A highlight of the two-day show was the appearance of the great inventor, Thomas Edison. The gigantic Gimbel’s Department Store was celebrating Founders Day, in honor of Adam Gimbel, who opened his first Gimbel trading post in 1842 in Vincennes, Indiana—the same year Father Sorin left Vincennes to found Notre Dame.

The biggest buzz of all in the great city was over the arrival of the German-made dirigible ZR-3, which commanded front-page headlines tracking its epic maiden voyage from Friedrichshafen, Germany to Lakehurst, New Jersey. “Z” stood for lighter than air. “R” stood for rigid construction, and the 3 indicated the model type. Captained by Dr. Hugo Eckener, the ZR-3 represented the height of technological advancements and the hope of future air travel, as the dirigible averaged a speed of 55 miles per hour. Citizens tracked the ZR-3’s daily progress and The New York Herald Tribune screamed headlines of its nearing arrival and confirmed radio contact on October 14. Other papers carried editorials stating that if the ZR-3 landed safely, it would hail the dirigible as having made a significant step forward in the development of regular transoceanic air service. Not to be overlooked was the fate of the British-built ZR-2, which blew up over Hull, England with the loss of 62 lives, or the airship Roma, a dirigible acquired by the United States from Italy that crashed near Hampton Roads, Virginia, killing 35 people.

Tickets for the big game were disappearing fast. Close to 60,000 people were expected, more than the capacity for baseball, though less than the record-setting crowd of more than 82,000 who a year earlier attended the world heavyweight title fight in which Jack Dempsey defended his championship with a second-round knockout of Luis Firpo, who had gained fame as the “Wild Bull of the Pampas.” Fans unable to attend the game were making plans to listen to the game on either of the two New York radio stations providing live coverage. On WEAF, Graham McNamee would be announcing; on WJZ, J. Andrew White would have the call. Many of those nestled in front of their radio sets would be families of Irish Catholic descent. Immigration and the rise of Catholicism in New York City had gone hand-in-hand during the last part of the 19th century. By 1924, the Archdiocese of New York City boasted more than 1.3 million Catholics, the largest ethnic groups being Irish and Italian. Close-knit Catholic communities, anchored by the local parishes and the nuns who taught in parish schools, dotted the city’s landscape from lower Manhattan and East Harlem to the Bronx and Staten Island. Being Catholic and “American” was a source of pride for the immigrant wave and their first generation

On Friday evening, Notre Dame spirit was riding high at a meeting hosted by the New York City Notre Dame club at the Inter-Fraternity building at Madison Avenue and 38th Street. The highlight came when Rockne addressed the gathering, giving his assessment of both upcoming games against Army and Princeton, giving the opponents proper respect while proclaiming the Irish ready to give their best.

Saturday, October 18 dawned sunny and pleasant in New York City. The Irish bused into the city from Rye for Mass, followed by breakfast at the Belmont Hotel. Conversation was minimal. The task was at hand. By late morning, the subway lines came alive with the bustling activity generated by the arrival of college football fans. Some fans arrived by exiting the subway station at 155th Street; others approached the stadium from atop the bluff along the Harlem River Speedway, descending a series of ramps that brought them to the ticket booths. Another set of ramps led fans down to the lower seating levels. Fans came across the Hudson River from the Bronx via the elevated trains of the Macombs Dam Bridge and the Putnam Bridge. Many entered on the Eighth Avenue side.

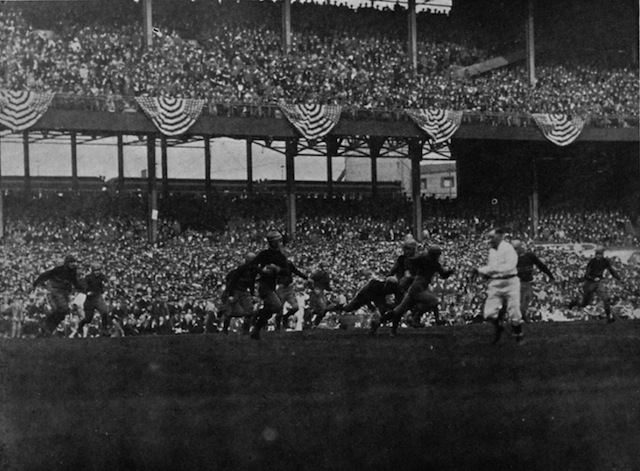

Fans carried pennants, lunch boxes, and jackets. Throngs arrived from a distance and appeared as columns of determined ants converging on the great stadium from several directions. Fans who hadn’t availed themselves of the advance sale jammed the ticket booths. Spread below was the green grass and grandstands of the Polo Grounds. It was almost as though the Emerald Isle was smiling on the Irish. But the crowd would be composed of a variety of people. Some, like the Irish-Americans eager to see Notre Dame, were true partisans. Others were drawn by the prospect of seeing two powerful gridiron elevens match wits, strategy, and strength. And still others looked forward to the great spectacle and pageantry of the day, highlighted by the entrance of 1,200 marching cadets greeted by loud, sustained cheering.

Rockne’s squad hit the field with full force, with three full elevens breaking off a series of dummy plays in perfect formation. Every ten yards, the men would set themselves, await the signal, then erupt in motion for another first down. The capacity crowd loved the show. It was Rockne at his entertaining best. Referee Ed Thorp blew his whistle and called the captains together at midfield. Adam Walsh, right hand in a cast, greeted Ed Garbisch with a left-handed handshake. The two had great respect for each other. As referee, Thorp too commanded great respect. At more than six feet and 200 pounds, he was a towering presence, and his intricate knowledge of rules and sense of fair play made him among the most respected of football officials.

Both teams started cautiously, like a great pair of heavyweights parrying and thrusting, each seeking the opponent’s strategy. Depending on field position, they might run only one play from scrimmage before punting, in the hopes of pinning the opponent deep in its own end. Every play was a fierce skirmish; every yard was hard-won. On one of the first plays of the game, Walsh went to block Garbisch, but the wily cadet jumped like a rabbit to avoid the hit. When he came down, one foot landed squarely on Walsh’s left hand, Garbisch’s cleats carrying his full 180 pounds. Walsh felt a searing pain radiating from his hand. This can’t be happening, he thought to himself. The game meant everything to him and his fellow seniors. The pain wasn’t subsiding, but it had to be overcome. Somehow, he willed himself to continue. Rockne’s faith in him as captain and leader of the Irish was being rewarded in a big way. Notre Dame, using its shift, deception, and teamwork, put together several sustained drives, one of which culminated in Layden’s short burst for a touchdown. At halftime, the Irish led, 6-0.

Up in the wooden press box, newspapermen were marveling at the precision and skill shown by Notre Dame in the second quarter. Rice held court with one group of sportswriters that included some of the biggest names in the business. There was Damon Runyan, who was called by William Randolph Hearst “the best reporter in the world,” had gained fame covering baseball and boxing for Hearst’s New York American; Gene Fowler, serving as backup to Runyan; Jack Kofoed, who had started his newspaper career in Philadelphia as an 18-year-old in 1912 and was now with the New York Post; Paul Gallico of the Daily News, at 27 already one of the most powerful sportswriters in the city; Davis Walsh, lead football writer for the United Press; and Notre Dame alum Frank Wallace, reporting for the Associated Press. Into this conclave strolled young George Strickler, Rockne’s publicist and South Bend Tribune correspondent. Part of his assignment from Rockne was to keep an ear open for analysis from the “big guys” in the newspaper business. Rockne always wanted to know, “What were they saying about us?” The conversation revolved around the exceptional work of the Notre Dame backfield in thwarting Army at every turn. “Yeah, just like the Four Horsemen,” Strickler piped up, recalling Wednesday’s movie. No reaction was noted from among the professional scribes. The confab eventually broke up as folks settled into place for the second half.

Notre Dame again started rolling, and the crowd was buzzing at the tremendous coordination and sophistication of the Irish attack. Notre Dame, lining up quickly, going into the shift and snapping off plays in rapid succession, seemed to be catching the Cadets flat on their feet. Midway through the quarter, Layden intercepted an Army pass, a big play typical for the senior, and lifted his teammates. The Irish neared the Army goal line, and Crowley made an amazing run, juking and stiff-arming Cadet opponents till he snuck into the corner of the end zone. Notre Dame led, 13-0.

The fourth quarter saw tremendous action as possession bounced back and forth between the two squads, each giving every bit of possible effort. Army cut the lead to 13-7 and was threatening again when Walsh, playing through excruciating pain, made a leaping interception to seal the soldiers’ fate. The Irish had prevailed, sending its followers—at the Polo Grounds, back in South Bend, and listening via the radio—into wild celebration. Both captains, the centers, had given their all. Garbisch wanted to enter the Notre Dame locker room to congratulate Walsh, but Rockne intercepted him. Thanks for the thought, the coach told him, but Walsh was in no shape to see anyone but a doctor. Walsh was taken to Roosevelt Hospital on 10th Avenue where an X-ray showed two small broken bones in his left hand to go with the three he already had in his right hand. Doctors urged Walsh to remain in New York for treatment, but he insisted on returning home with his team.

The crowd of 1,200 who packed the Palais Royale in South Bend for the News-Times’ grid-graph whooped, clapped, and sang along with the Lucky Seven as the combo played the Victory March over and over. It had been a raucous afternoon, and the experiment was dubbed a huge success. Fans didn’t have to stand outside straining to hear an announcer from a megaphone; they had a complete description of the game, lots of lively music, and like-minded Notre Dame fans with whom to cheer. The newspaper enthused: “Had Captain Adam Walsh and his … fighting gridders heard the cheers that went up for them here, who knows but that the Notre Dame score might have mounted.”

On campus, the students packed the gym had shouted themselves hoarse in the excitement. The Notre Dame band kept playing. Spilling out of the gym, students cheered and shrieked in a celebration that lasted into the night. It was reported, “echoes reverberated over the university buildings as the student body in true Notre Dame fashion celebrated the impressive victory of the Fighting Irish.” The students, led by the band, paraded across campus, hailing their heroes. The march culminated at the Main Building, where President Father Matthew Walsh addressed the crowd. Standing atop the building’s steps, it was an entirely different feeling than that of five months earlier, addressing students from atop the Civil War statue downtown during the Klan incident. As was his custom, in hailing today’s heroes, Father Walsh recounted the famous 1909 Michigan game and Pete Vaughan’s reputed smashing of the goal post to claim an Irish victory. After the demonstration, plans were made for a welcoming ceremony to greet the team on its arrival back in South Bend Sunday afternoon.

At newspaper offices around New York and across the country, columns of coverage of the big college games were being prepared for the Sunday papers. It had been a monumental day for the sport. In Urbana, Illinois, “a flashing, red haired youngster, running and dodging with the speed of a deer, gave 67,000 spectators jammed into the new $1,700,000 Illinois Memorial stadium, the thrill of their lives when Illinois vanquished Michigan 39 to 14 in what probably will be the outstanding game of the 1924 gridiron season in the west.” Harold “Red” Grange had taken the opening kickoff and raced 95 yards for a touchdown to christen the new building. He then broke loose for touchdown runs of 65, 55 and 45 yards—all before the first quarter ended. Grange finished the day with five touchdowns and 402 total yards. His feat was “declared by gridiron experts to be one of the most phenomenal in the history of the game.” Newspapers scrambled to find pictures and sketches of the Illinois star to run with their game coverage. In addition to the 67,000 at Illinois and 60,000 in the Polo Grounds, 50,000 gathered in Cambridge to see Harvard defeat Holy Cross, 12-6, and crowds of 45,000 were tallied for both the Yale-Dartmouth and Penn-Columbia games.

Reporters covering the Army-Notre Dame batted out stories that covered a variety of elements of the big game. The New York Times, in addition to expansive game coverage, went into great detail on the arrival of the West Point band and corps of cadets, the pageantry and atmosphere of the contest. Westbrook Pegler, whose account was dispatched to a number of papers nationwide, commented on the makeup of the 60,000: “It was a strange crowd which filled the permanent stands and bleachers because Notre Dame had brought only a few non-combatants along to kick up a noise, and the Army’s cadets filled only a pocket of the capacious stadium. It was largely a non-partisan crowd, come to see a good game of football.”

Damon Runyon, writing for the New York American and the Hearst syndicate, took a different approach, opting to focus on the Army mule mascot and the blanket that draped the mule. He thought Notre Dame fans would emulate the tradition shown by victorious Navy fans, who would charge from the stands after defeating the Cadets and snatch the mule’s blanket. Although the enthusiastic Notre Dame fans never approached the mule, Runyon stuck with his idea for the lead. Young Frank Wallace was torn between his allegiance to Notre Dame and the need to write a lead for the Associated Press that would appeal to a diverse reader base. He managed to do both when he wrote: “The brilliant Notre Dame backfield dazzled the Army line today and romped away with a 13 to 7 victory in one of the hardest-fought of the intersectional series between the two teams. More than 50,000 people saw the game.”

Grantland Rice, in the evening twilight and gathering chill, sat at his typewriter in the Polo Grounds press box and pondered his opening. Something about Strickler’s halftime comment and the imagery of horses stuck in Rice’s mind when he reflected on the Notre Dame backfield. He recalled the 1923 game at Ebbets Field, when an out-of-bounds play brought to mind the possibility of being trampled by a runaway team of horses. It all clicked. His fingers hit the typewriter keys:

Outlined against a blue-gray October sky, the Four Horsemen rode again. In dramatic lore they are known as Famine, Pestilence, Destruction and Death. These are only aliases. Their real names are Stuhldreher, Miller, Crowley and Layden. They formed the crest of the South Bend cyclone before which another fighting Army football team was swept over the precipice at the Polo Grounds yesterday afternoon as 55,000 spectators peered down on the bewildering panorama spread on the green plain below.

A cyclone can’t be snared. It may be surrounded, but somewhere it breaks through to keep on going. When the cyclone starts from South Bend, where the candle lights still gleam through the Indiana sycamores, those in the way must take to storm cellars at top speed. Yesterday the cyclone struck again, as Notre Dame beat the Army, 13 to 7, with a set of backfield stars that ripped and crashed through a strong Army defense with more speed and power than the warring cadets could meet.

From there, Rice described “the driving power of one of the greatest backfields that ever churned up the turf of any gridiron in any football age.” He noted the following on the second quarter scoring drives: “the unwavering power of the Western attack that hammered relentlessly and remorselessly without easing up for a second’s breath.” Rice paid particular homage to the speed of the Irish attack, the precision with which it worked, and the consistently effective blocking it used to advance the ball on the ground.

Rice also had high praise for Notre Dame’s defensive play. “When a back such as Harry Wilson finds few chances to get started you can figure upon the defensive strength that is barricading the road. Wilson is one of the hardest backs in the game to suppress, but he found few chances yesterday to show his broken field ability. You can’t run through a broken field until you get there.” He concluded by stating “we doubt that any team in the country could have beaten Rockne’s array yesterday afternoon, East or West. It was a great football team brilliantly directed, a team of speed, power and team play. The Army has no cause for gloom over its showing. It played first class football against more speed than it could match. Those who have tackled a cyclone can understand.”

The editors at the Herald Tribune felt the quality of Rice’s piece and the significance of the game merited front-page play, and so the story ran on the front of Sunday’s paper—page one, column one at the top left-hand corner. Rice was not totally alone in developing the equine theme. Heywood Broun, a fine wordsmith writing in the New York World, wrote that Notre Dame “defeated the West Pointers with sweeping cavalry charges around the ends…They were light horsemen, these running backs of Notre Dame, but they swung against the Army ends with speed and numbers. The players were run wide and again and again, some unfortunate soldier sentinel would race all the way across the gridiron and over the sidelines without ever getting contact with any one but one of the interfering outposts.”

Before boarding the train home, Strickler stopped at a newsstand and grabbed copies of the “bulldog” early editions of the Sunday papers. Reading Rice’s lead, he could barely believe his eyes. According to Strickler, he sent a wire to his father back in South Bend, advising Mr. Strickler to round up four horses for a publicity photo he wanted to have taken. In the coming days and weeks, the notion of Notre Dame having not only a “wonder team” but a backfield of biblical proportions would sweep across the country. Rice’s phraseology would gradually make its way into other sports writers’ descriptions. William F. “Bill” Fox, Jr., a 1920 Notre Dame graduate, joined the sports staff of the Indianapolis News as a reporter. He saw the 1924 team, as long as it continued to perform at a high level, as a major national sports story. Fox strongly encouraged Strickler to take advantage of the opportunity Rice’s story presented and offered to help in any way he could.

During the week of practice before the Princeton game, Strickler enlisted his father, who had more experience around animals because of his job on the university farm, to help with a publicity photo shoot. His assignment was to round up four riding horses for the famous backfield to mount. Instead, he came up with four well-worn workhorses, of different sizes and condition. Strickler arrived at the practice field, explained the stunt to the guard, and brought the horses onto the field. The commercial photographer Strickler hired for the shoot, Mr. Christman, was already there. The four players were summoned, and they began to look askance at one another. Except for Stuhldreher, who had handled horses while delivering groceries for his father’s store, the four had little equine expertise. But more than that, each knew that being thrown from a horse could cause an injury that would, in an instant, put an end to their participation in a magical season. All that risk just for a photograph? With the players anxious, and Rockne not wanting his practice interrupted any more than necessary, it was a quick photo shoot. A couple of shots were taken, the players were on their way, and Strickler guided the horses off the field.

Once the prints became available, Strickler went to work distributing the photo. His first sale was to Pacific & Atlantic, a national news photo agency. Every time P&A syndicated the photo in another newspaper, Strickler received a royalty. One by one, the major newspapers in the country ran the photo. The nickname and photo became vehicles for the sporting public to connect a personal story to the feats of a team, which was picking up admirers by the thousands. The efforts of Rice, Strickler, Fox, and others aside, a rapidly growing fan base, especially one of Irish-Americans, was eager to embrace the story of the college boys representing the school in South Bend. Rockne was delighted to see this particular group, which had worked so hard for four football seasons, reap the rewards of their efforts.

The new-found fame seemed to have little direct impact on the Irish players. There were injuries to heal, exams for which to study, and daily activities that demanded their attention. The fellows also possessed a natural modesty of a group of down-to-earth players who simply loved the game of football. After returning from the Army game, Layden wrote his romantic interest, Evelyn Byrne, back home that “against the Army, I played a few minutes, and was fortunate enough to score a touchdown.” As for the upcoming Princeton game, Layden wrote, “I hope I am again fortunate enough to make the trip.”

Layden, indeed, made the trip back East just four days after returning from New York. Though banged up from the battle with Army, all of the Irish, except Walsh, would be able to play against Princeton. That included Stuhldreher, whose throwing arm had been giving him problems the past several weeks. Before the Army game, Rockne told him there was a doctor in New York who had prepared a new liniment meant to “limber dead nerves” like nothing else. “Before the game,” Stuhldreher noted, “they worked on my arm, massaging the liniment well into the skin so that its healing oils penetrated the muscles, and put a hot pad on it.” In the game, Stuhldreher was able to use his arm as if there were nothing wrong with it. The same procedure was used for the Princeton game, and Stuhldreher again felt fine. Only after did Rockne tell him “that this wonderful liniment was none other than the one they used all the time at Notre Dame. He had put it into a different bottle so that I would think it different.”

_______________________________________________________

For more information on how to order the award-winning book Coach For A Nation, click here.

To order author Jim Lefebvre’s first-award winning book Loyal Sons: The Story of Notre Dame Football’s 1924 Champions, click here.