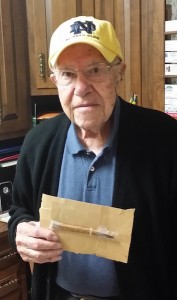

Art Huber is just six months shy of his 100th birthday.

Yet, when he closes his eyes and remembers, he can still clearly see himself as a 7 or 8-year-old, in the early 1920s, playing in the parks and backyards of his hometown, little Fort Atkinson, Iowa, choosing sides for ballgames.

“My team was always Notre Dame.”

“We were Catholic…you just naturally followed Notre Dame,” Huber says. “And Knute Rockne…he was my hero. When he lost his life in the plane crash, well…” he says, voicing trailing off.

The love for Notre Dame never left him. He was a good student in high school, excelled in baseball, played a little basketball (“Our school had no indoor gym”), and no football (“We were too small a school to have a team.”). Graduation in 1932 was approaching. He hadn’t given much thought to his plans after high school, but his father wanted him to attend college.

“I said OK – only if I can go to Notre Dame.”

And so began “a wonderful four years” which included four years as a member of the Notre Dame Band. In the decades that have followed, thousands more enjoyed marching for the Fighting Irish. This weekend, nearly 1,000 will gather to participate in Alumni Band festivities. Art can’t be there in person, but will be with his fellow ND Band alums in spirit.

But even with Band, Art did make an obligatory effort to try out for football, even though, “I didn’t even know how to put shoulder pads on; they were new to me.” While football wasn’t his sport, he excelled in baseball, and made Coach Jake Klein’s traveling squad by his junior year.

The Band was much smaller in Art’s time; he was was one of “about 10 clarinets” in the Band, which totaled 84 members. He remembers playing for Commencement in 1935, when the speaker was President Franklin Roosevelt. Playing in the Band was a major commitment, as legendary director Joseph Casasanta drove the players to excellence in marching and playing.

Then, as now, the Band traveled to select major away games. In 1932, Art’s freshman year, it went to the University of Pittsburgh. There were trips to Evanston for games against Northwestern. In 1934, a trip to Cleveland for the annual clash with Navy highlighted the season. And in 1935, Art’s senior year, the Band went on two major excursions – to Yankee Stadium for the Army game, and to Columbus, Ohio, for the long-awaited first-ever meeting between the Fighting Irish and the Buckeyes of Ohio State.

Both teams were undefeated coming into the game, yet some Ohio State writers were predicting a huge Buckeye victory. More than 81,000 crammed into The Horseshoe, and while Notre Dame had played before big crowds in the past, they were almost always on neutral fields, or stadiums that included many Irish fans. This venue seemed intimidating – to the team, and even to the Band.

And when the Buckeyes held a 13-0 well into the fourth quarter, it looked like it would be little more than a hard-fought defeat.

That’s when Notre Dame back Andy Pilney went to work. A pass by Pilney. A run by Pilney. Another pass. A pass to Francis Gaul reached the two-yard line. Fullback Steve Miller took it over. The point was missed. 13-6 Buckeyes.

The Irish defense held, and pretty soon Pilney uncorked a pass that Wally Fromhart caught on the Ohio State 33, and outran the defense for a TD. But again, no extra point. “I can still see Wally Flomhart on the point-after,” says Art Huber. “He kicked the dirt, the ball went nowhere, and we were still behind, 13-12.”

An onside kicked failed, and the Buckeyes took over on their 47, needing only to run out the clock. But the Irish defense surged toward the ball, knocking it loose, and Hank Pojman, a backup center, recovered for ND.

Francis Wallace, in his wonderful book “Notre Dame From Rockne to Parseghian,” paints the picture: “The backfield shifted…the ball came back to Pilney. …receivers covered. So Andy took off, popping through the cup of foaming rushers, twisting and turning….Four times it seemed they had him…drove until four of them knocked him out of bounds stopping the clock. Pilney wasn’t getting up.”

Pilney, who had led the heroic comeback, was carried to the bench on a stretcher with 30 seconds remaining. Into the game came little-used backup Bill Shakespeare, the senior from Staten Island, N.Y. His first pass went right to an OSU defender, who dropped the ball. Then, with just seconds left, Shakespeare lofted an aerial into the end zone that Wayne Millner caught to complete the miracle finish. Notre Dame wins, 18-13.

“Shakespeare throws the winning pass to a guy (Millner) I had helped get through English class,” said Huber. “Everyone in the stands stood there, just shellshocked.” The epic battle was later named by sportswriters as the best football game played in the first half of the century.

Huber and his Band mates led the post-game celebration, marching “across the field” and then continuing “all the way downtown, right down to the heart of the city.” They followed a Notre Dame fan driving a Ford Roadster Turtleback – carrying a length of the wooden goalpost as a sign of captured treasure.

Huber still proudly owns a slice of wood from that goal past. As he does the sturdy Buescher clarinet he marched with that day – and still plays!

After graduating from Notre Dame in 1936, in the midst of the Depression, Huber was chosen to study the General Motors accounting system at a facility in Flint, Michigan. From there, he worked in GM accounting at Norwalk, Ohio, outside Cincinnati, for nearly a decade.

These days, he no longer travels to games. But he follows the Irish closely, keeping up with the news online and watching every game on TV.

And this weekend’s Stanford game brings another interesting twist – the somewhat mixed loyalties of Art’s eldest son Joe. He’s a 1964 Notre Dame alum, and 1967 grad of the Stanford Law School. Joe is a Superior Court of California Judge in San Jose, lives in Palo Alto, and has served as mayor of Palo Alto. He attends the Cardinal’s home games.

At Notre Dame Stadium on Saturday, some 800 Alumni Band members will join the nearly 400 members of today’s Band of the Fighting Irish. The musical extravaganza will pay tribute to the three pillars of the Notre Dame Band – excellence, tradition, and family.

Back in tiny Fort Atkinson, Iowa, Art Huber will be in his usual spot in his long-time home, watching the game, cheering on his Irish…and recalling fond memories as a member of “the oldest band in the land.”