By Jim Lefebvre

An author who undertakes the telling of a significant life takes on an awesome responsibility – assuming he or she is serious about truth-telling. For the biographer of integrity, there will be years of research, mountains of materials to sift through, speculation and supposition around certain aspects of the life being studied.

And so it was with my five years and more of research on the life of Knute Rockne.

Long, grueling days poring over correspondence and documents at the Notre Dame Archives and other libraries and archives across the nation; eye-straining hours deciphering newspaper microfilm; interviewing descendants of Rockne’s players and coaches; reading innumerable accounts of Rockne’s life, the development of Notre Dame, and the people and events that shaped those remarkable times.

Ever sifting and winnowing, assessing each tiny bit of information for its relevancy and accuracy. Accumulating massive files of research on every aspect of the story.

Then, finally, writing. Agonizing over each sentence in a 180,000-word tome, always asking: Is this the most truthful representation of all that I have learned?

When it was published in 2013 – on the 100th anniversary of Rockne’s pivotal senior season as captain of the undefeated Irish – my biography Coach For A Nation: The Life and Times of Knute Rockne set the bar, far eclipsing any previous work on the iconic coach.

“Jim Lefebvre has thoroughly researched and written the definitive piece on this American hero.” said Kent Stephens, curator of the College Football Hall of Fame.

The Independent Publisher Book Awards – the highest honor in small-press publishing – agreed, including Coach For A Nation among its 2014 medal winners for overall excellence.

Since that time, it has been my privilege to travel the country speaking on the life and legacy of Coach Rockne, and I have gone on to found the Knute Rockne Memorial Society and the Knute Rockne Spirit of Sports Awards (the third version taking place this Oct. 11 in South Bend.) We are currently working to create a documentary film based on Coach For A Nation.

At my talks and elsewhere, I have been asked all manner of questions about Rockne’s life and impact.

Now there’s this one: What about this theory that his plane was bombed by the mob?

Oh, yes, the “mob bomb” theory. Sometime during my research, in 2012, I spent an inordinate amount of time on this question. A proponent of the tale had sent me a massive binder of “evidence” – mostly news articles of the Jake Lingle murder in Chicago and the mob’s intent to silence a witness, Rev. John Reynolds, CSC. That may well have happened. But everything that followed – Reynolds gave his airline ticket to Rockne at the last minute, and the mob bombed the plane in its attempt to silence Reynolds – is clouded in a fog of mystery. There was nothing approaching any sort of proof that this tale was true.

It would have been completely irresponsible on my part to include it in a truthful telling of Rockne’s life and death.

Now, in the Spring 2019 issue of Notre Dame Magazine, comes a series of articles under the tag “Do You Believe It?” And one of them is headlined “Mob Bombs Rockne Plane.”

No, I don’t believe it. Why not? Because there’s no physical evidence, then or now, of a bomb causing the Rockne air crash.

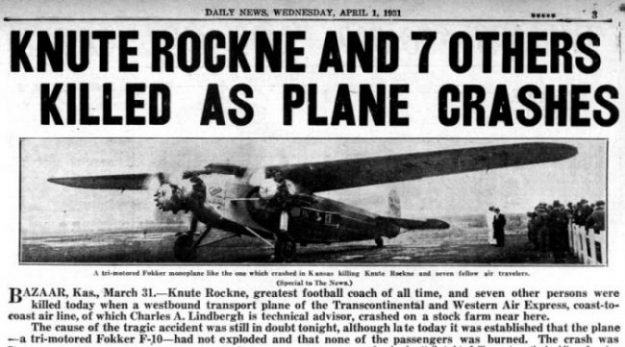

As we detail in the pages of Coach For A Nation, planes designed by Dutch aviator Anthony Fokker had been problematic for decades. And the crash of Transcontinental & Western Airlines flight 5 (sometimes referred to as flight 599) on March 31, 1931 in the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas spelled the end of wooden-winged aircraft like the Fokker F-10A; and spawned the advent of all-metal construction, and the start of a much more vigorous role for the federal government in airline regulation, aircraft safety and crash investigation and reporting.

The official investigation (far from being indecisive) and all subsequent analyses by aviation experts, have agreed:

Challenging weather between Kansas City and Wichita that morning rendered the craft’s instruments useless and led to some extreme flying measures as the plane, seriously off-course, was squeezed between the low cloud cover and the nearby hills, the stress from which exposed the compromised wooden core of the aircraft. One wing completely separated from the plane, which then plummeted to the ground, killing all eight men aboard.

But what about the newspaper stories in 1933 about a bomb?

Yes, the South Bend News-Times published a shocking story in early 1933, which was picked up by other papers, citing unnamed sources that were never identified. Hmmm, a sensational story by a newspaper locked in a heated battle for circulation with the South Bend Tribune. Look up the phrase “yellow journalism” and get back to me. The News-Times, despite its extreme efforts to add subscribers, never earned a profit during that time, and finally folded in 1938.

“Particularly in those days, it was all-too-common for media airplane-crash stories to colorfully ‘fill in the details’ with dramatic accounts exaggerating or simply fabricating what happened,” notes aviation expert and historian Richard Harris. “Simply ‘falls from sky’ wouldn’t sell as many newspapers as ‘explodes, crashes in flames.’”

And no, the story didn’t get overwhelmed by the Depression and the rise of Hitler. More recent research has found that the FBI and other federal authorities gave the story no credence whatever.

“That story never found legs or corroboration when first published — or since,” says Dr. Greg Cloyd ’78, long an avid student and collector of all things Rockne. “It was a sexy urban myth about a famous person and a widely-publicized air disaster. That sells newspapers!”

“Generally,” notes Samuel G. Freedman, a professor of journalism at Columbia University, “circulation wars of that time offered a persistent temptation for editors, reporters, and publishers to be reckless with facts and flagrant with speculation.”

Says Nils Rockne, the coach’s grandson and official family spokesman: “This story is not truthful in any way, shape or form. It comes up every few years, but still is just plain baloney.”

And Jerry McKenna, world-renowned sculptor whose images of Rockne stand at Notre Dame Stadium, downtown South Bend and Voss, Norway, adds: “The ‘mob bomb theory’ dishonors a great man.”

But it’s right there in the crash investigation: “First reports were that the plane exploded.” Yes, and a lot of ‘first reports’ are proven wrong once actual investigation takes place. A teenager on the ground said he heard what sounded to him like an explosion; another said he thought he heard cars racing on the nearby road. None of their statements prove anything about a “bomb.” Experts agree there was likely some backfiring in the final desperate moments of the flight.

Again, there was no physical evidence of a “bomb” (or even an explosion) found at the crash site, or anywhere else.

But such an expert as Fokker himself examined a small piece of the wing and concluded, “Material and glue joints all perfect.” Really? That’s evidence? The designer of the plane, about to see his entire company and career crash, is a credible source of analysis? Please.

But Father Reynolds himself said it was so. In a rambling interview shortly before his death, the 92-year-old priest-turned-Trappist-monk makes a number of unclear, sometimes contradictory statements, at one point saying the mob was not after him. To use that as “evidence” of a bomb is disingenuous at best.

Is it a fascinating tale of murder, intrigue, revenge, and mob power emblematic of 1920s Chicago?

Yes.

Did it result in a bomb bringing down Rockne’s flight?

Not according to any honest reckoning of the facts.

The “mob bomb” fairytale assumes a cover-up of epic proportions – by the investigations that followed the crash, and the many aviation experts who have analyzed it in the decades since then. The amount of speculation, supposition, and fabrication needed to believe such a tale is staggering.

So What Really Happened?

As with any complicated story, some context is needed.

First, some background on Anthony Fokker and his planes, starting with their role in the Great War…

In Germany, the name Fokker became synonymous with early aviation warfare. Rising to prominence as a builder of biplanes and triples used extensively by Germany in the war, Anthony Fokker made aerial combat possible by inventing a device to synchronize machine gunfire with propellers. An opportunistic aviation businessman, Fokker’s early success was due as much to good timing and marketing strategies as to engineering genius. His reluctance to invest in research and development led to his struggles with quality control throughout his career and played a role in the eventual decline of his aeronautical empire in later years. Rittmeister Manfred von Richthofen, better known as the Red Baron, flew more than 80 war missions in the premier German aircraft—Fokker’s D.I design. Fokker claimed, “In official tests, the D.I proved to be the fastest and most efficient fighter available.” Official records, however, offered a different view. Documents included a statement that indicated while from a distance the Fokker D.I looked good, a closer examination revealed flaws in both the design and workmanship.

The main cause was Fokker’s apparent insistence on using the cheapest materials available regardless of their fitness for the task for which they were being bought. Fokker often disregarded adequate quality control of both components procured and his standard of workmanship in his production workshops. An examination of the records of virtually all of Fokker’s wartime aircraft revealed that each went through a period when defects in either its manufacture or the materials used for its construction were exposed and later rectified at his expense. At one time, the use of his aircraft for combat was banned and he came close to being prosecuted on the grounds that he was both defrauding the German government and endangering the lives of German pilots.

When the November 1918 Armistice stopped all German aircraft production, Fokker was left with silent factories. He then smuggled his money out of Germany to Holland via boats and suitcases, established Dutch nationality, and began manufacturing Dutch aircraft. The U.S. Air Service, which had been impressed with some of Fokker’s designs, sent officers to Holland to negotiate purchases of his new prototypes. This in turn led Fokker to make multiple trips to the United States and to eventually establish the Atlantic Aircraft Company, a subsidiary of his Dutch-based company, in New Jersey. Thus Fokker began to build aircraft in the United States, sidestepping American prejudice against the purchase of foreign aircraft for national airlines. He eventually established permanent residence in the United States in 1925. In 1926, he became an American citizen and established the Fokker Aircraft Corporation with headquarters in New York City, becoming an active participant in the expanding airplane manufacturing industry.

The late 1920s brought a dizzying array of activity in the air industry, as it adapted its technology for mass passenger travel. A complex series of mergers and stock market takeovers created an ever-changing lineup of companies and individuals in the industry. For someone such as Anthony Fokker, developing new models was a financial stretch; he could not match the latest designs of other companies without major new investment. Eventually, his F-10 tri-motor drew the attention of Dillard Hamilton, an inspector for National Parks Airways. Hamilton wrote a letter to Gilbert Budwig, director of air regulation for the Department of Commerce, expressing concerns about not being able to inspect the internal structure of the Fokker wings because they were bonded together with glue. Checking the wing spars and the internal bracing would involve removing the plywood covering of the wing, thus damaging it. Subsequently, the U.S. Navy tested the F-10A, found it unstable and rejected it for naval use.

Fokker maintained that operators didn’t have to worry about the F-10A’s wing structure as long as the plywood skin remained glued to the spars. That prompted the Aeronautics Branch to take a closer look at the wings, particularly when maintenance couldn’t be performed without ripping off the plywood skin. On March 30, 1931 – the day before the Rockne crash – the Aeronautics Branch felt it had enough evidence to justify grounding all F-10As immediately.

Investigation of commercial airline crashes began in the mid-1920s. The Air Commerce Act of 1926 was enacted and the Commerce Department, through its Aeronautics Branch, proceeded to draft safety regulations and establish air crash investigation methods. But there had already developed much tension between the federal government’s dual roles in promoting air travel and ensuring its safety.

In 1930, the Commerce Department found that 26 passengers and 10 airplane pilots had been killed in 47 accidents on scheduled airlines. Yet none of these crashes created a demand for greater safety and detailed investigation with reports being made public… until March 31, 1931.

The Morning of March 31, 1931

Rockne was scheduled to fly out of the Kansas City Municipal Airport. The flight was delayed 45 minutes to await the mail, but at 9:15 a.m. agent R.S. Bridges waved Flight 5 out of the gate area. Minutes later it took off, into an overcast sky with light snow falling, ceiling 400 feet, visibility seven miles, light winds and a temperature of 37 degrees. But it was just 6 degrees at Dodge City; to reach its first stop at Wichita, Flight 5 would have to penetrate a sharp cold front. With the cold air meeting moist, warm air to the east, there were likely to be clouds, fog, ice, and low ceilings.

At the controls was Captain Robert Fry, who had been with the airline since June 1929. A native of football-crazy Canton, Ohio, Fry had grown up in Milwaukee and enlisted in the U.S. Army in the Great War. Later, in the early 1920s, before becoming a civilian pilot, Fry had a hitch as a gunnery sergeant and fighter pilot with the U.S. Marines’ air service, serving in Guam and China. During one mission in China, his plane was shot, and he was forced to bail out into a rice paddy. On the morning of March 31, Fry had breakfast with his wife Mary and, before leaving for the airport, presented her with a new photo of himself in his captain’s uniform. She wished him “a good and safe flight.” Such a flight was not always a guarantee. Just months earlier, Mary had buried her sister, well-known flyer Clair Fahy, a star of the 1929 Women’s Air Derby, after she crashed in the Nevada desert. Clair’s husband, Herbert J. Fahy, was an aeronautical record holder and Lockheed test pilot before he died in a crash, a few months before Clair’s death.

The plane, a Fokker F-10A Trimotor, bore a Department of Commerce number NC 999 E. The Fokker Aircraft Company of Teterboro, New Jersey had manufactured the plane, commissioned on October 29, 1929. Valued at $80,000 when new, it now had logged 1,887 hours of flying time. At 14,000 pounds, the F-10A was heavier than its predecessor, the F-10, and featured a longer, one-piece wing, 79 feet; the fuselage was 50 feet in length. Three 450-horsepower Pratt & Whitney engines with triple-headed propellers powered the craft to a cruising speed of 123 miles per hour.

The Fokker F-10A had been inspected a few days earlier by TWA mechanic E.C. “Red” Long, who would later note that “the (plywood) wing panels were all loose on the wing. They were coming loose and it would take them days to fix it, and I said the airplane wasn’t fit to fly and I wouldn’t sign the log.” But a superintendent told Long TWA needed the aircraft, to meet its contractual obligation to fly U.S. mail. “I don’t know who signed the plane off, but they took the airplane…Nobody was safe in that airplane.” But off it went anyway.

Paul Johnson, an airmail pilot flying a faster craft than Fry’s, left Kansas City 15 minutes after Fry, but passed Flight 5 over Emporia, about 100 miles from Kansas City. Johnson later reported encountering fog, cloud cover, and icing, forcing him to fly close to the ground. At 10:22 a.m., Fry’s co-pilot Jess Mathias radioed the station in Wichita and was told the weather was clear there. But Mathias responded, “The weather here is getting tough. We’re going to turn around and go back to Kansas City.” Fry was flying low to the ground, under the low ceiling. A few minutes later, the Wichita agent confirmed that weather there was clear, and Mathias and Fry apparently decided to try Wichita after all. If they couldn’t make it, Mathias said, perhaps they would turn back and go as far as Olpe, a field sometimes used for refueling emergencies.

In a final transmission at 10:45 a.m., Mathias said, “It’s getting tighter. Think we’ll come on to Wichita. It looks pretty bad.” Flying so close to the ground, with heavy clouds and a hilly terrain, just making a simple 180-degree turn would have been treacherous. By now, the flight had also drifted off course to the west. It was possible Fry and Mathias were navigating via the “Old Iron Compass.” Pilots, without instrumentation or radio navigation, would often follow railroad tracks, and the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway connecting Kansas City and Wichita, was several miles west of the flight’s original course. Mathias told the Wichita agent he and Fry were “too busy” to talk; they were likely squinting through rain-slicked windshields, trying to follow the rail tracks just 300 feet or less below them.

Aviation experts reconstructing the crash described the likely situation:

“‘Scud-running’ is stimulating flying…Errant wisps of cloud would have blocked their vision, first occasionally, then more often. There would be breathless moments when the rails seemed lost for good. The only remedy was forward pressure on the control column and a loss of 25 or 50 ft. The right of way would reappear clearly for a while, but then the process would begin again.

“A deadly situation was developing…the clouds were almost touching the hilltops. Once the crests disappeared, the Fokker would be trapped and the option of climbing to at least temporary safety forfeited, since to do so would involve a good probability of crashing into the hidden higher ground. They were being squeezed between the ground and the clouds. Proximity to the ground, the clouds and the hills would have made a simple 180-degree too dangerous.”

Experts believe Fry “firewalled” the throttle to raise the aircraft’s nose and climb into the overcast. There, they would rely on the Fokker’s instruments: tachometers, magnetic compass, airspeed indicator and the gyroscopic turn-and-bank indicator. Under ordinary circumstances, instrument flying would have kept the wings level and controlled airspeed.

“But circumstances were not normal that morning, and this is probably the key to NC999E’s last minutes. First of all, lateral stability had been compromised. Apparently on the advice of a manufacturer’s representative, both allerons – the small hinged portion of the wing, used to make an airplane roll, or turn around its long axis – had been readjusted to ride an inch above the wing’s trailing edge.

“The airplane would now bank on small control-wheel inputs, but would require unusually heavy control to recover, placing a premium on keeping the wings level by reference to the turn-and-bank indicator. Unknown to the pilots, that instrument was dying. The next instrument to go would be the airspeed indicator, as ice choked the pitot tube and covered the static ports.

“Deprived of these key references, the disoriented pilots would have been unable to keep the airliner from entering a spiral dive. The Fokker was now out of control, nose down and accelerating. When screaming engines and runaway tachometer readings alerted the pilots to their predicament, Fry, in a futile effort to slow the machine, would have pulled the throttles right back, producing the backfiring heard on the ground seconds before the airplane crashed.”

On the ground, in the rolling Flint Hills of eastern Kansas, Robert Blackburn, a rancher feeding a herd of cattle near the crossroads of Bazaar, heard an airplane overhead, apparently headed south toward Wichita. Edward and Arthur Baker, teenage sons of Seward Baker, who operated a ranch near Matfield Green, were moving cattle when they heard an airplane’s engine around 10:30 a.m. They strained their eyes, but the cloud cover and fog prevented them from seeing the craft. They cupped their ears to the skies, and heard sounds that seemed to indicate the plane was increasing speed. Then it began backfiring. Finally, they heard no engines at all—followed by the sounds of a crash.

On the ground, in the rolling Flint Hills of eastern Kansas, Robert Blackburn, a rancher feeding a herd of cattle near the crossroads of Bazaar, heard an airplane overhead, apparently headed south toward Wichita. Edward and Arthur Baker, teenage sons of Seward Baker, who operated a ranch near Matfield Green, were moving cattle when they heard an airplane’s engine around 10:30 a.m. They strained their eyes, but the cloud cover and fog prevented them from seeing the craft. They cupped their ears to the skies, and heard sounds that seemed to indicate the plane was increasing speed. Then it began backfiring. Finally, they heard no engines at all—followed by the sounds of a crash.

The Baker brothers rode their horses in the direction of the backfiring and were the first upon the horrific crash scene. The fuselage was badly burned, and the wing lay several hundred yards to the southeast. Bags of mail dotted the landscape. Debris was strewn for nearly as far as the eye could see. And, north of the wreckage, five bodies lay motionless. One, about 20 feet from the plane itself, was Knute Rockne. All eight men had died instantly upon impact.

In the coming days, crash investigators would discard a couple of possible causes for the crash before focusing on deterioration of the wooden wing spar. As the Fokker was likely in a spiral dive when it broke up, excessive speed – through flutter – was seen as contributing to the accident. Flutter occurs when airspeed causes a wing or control surface to vibrate, and once initiated it can destroy the structure before the pilot can slow down. Once begun, flutter would almost instantly have twisted the wing from the Fokker like a banana from its bunch.

And what had weakened the wooden core of the plane?

The Fokker multicellular wing structure employed a series of glued wooden joins. Water is the enemy of that form of construction, and it was known in the industry that if the wood retained 20 per cent or more of moisture, the joint was likely to fail, The F-10A maintenance manual stressed that it was “absolutely necessary that the finish and covering of the wing be kept in good condition and waterproof. Months earlier, the Aeronautics Branch of the U.S. Department of Commerce had been warned the difficulty in inspecting F-10A wing interiors for water damage made the aircraft unsafe.

After the crash, government inspectors found evidence of delamination and failed joints. Coupled with the likely flutter-inducing buffeting as the slipstream swirled around the loose plywood panels, Flight 5 barely stood a chance.

On May 4, 1931, Col. Clarence M. Young, assistant sectary of Commerce for Aeronautics, barred all F-10s and F-10As built during 1929 from carrying passengers until they had been thoroughly inspected. Fokker airliners were now pariahs, and the company quickly died. The era of wooden-winged aircraft was basically finished.

Knute Rockne and seven others were killed in an accident precipitated by difficult weather conditions, which forced two pilots to take some extreme risks, in an aircraft not built or equipped to withstand the stress.

Attributing the crash to a bomb planted by the mob is going down the rabbit hole of conjecture, supposition and fabrication.

Portions of the previous story first appeared in Coach For A Nation: The Life and Times of Knute Rockne. © 2013, All rights reserved.

References

Allen, Richard S. “More on the TWA Fokker F-10-A Crash,” Journal of the American Aviation Historical Society; Fall, 1986.

Dierikx, Marc. Fokker: A Transatlantic Biography. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997.

Eckert, William G., M.D. “The Rockne Crash,” American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology; Vol. 3, No. 1; March, 1982.

Fokker, Anthony H. and Gould, Bruce. Flying Dutchman: The Life of Anthony Fokker. New York: Arno Press, 1931.

Friedman, Herbert M. and Friedman, Ara Kera, “The Legacy of the Rockne Crash,” Aeroplane magazine, May, 2001.

Harris, Richard. “Fans, Family Remember the Crash Heard ‘Round the World.” http://home.iwichita.com/rh1/rockne/ April 3, 2011.

Johnson, Randy, M.A. “’The ‘Rock’: The Role of the Press in Bringing About Change in Aircraft Accident Policy.”Journal of Air Transportation World Wide, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2000.

Komons, Nick A. “Bonfires to Beacons – Federal Civil Aviation Policy Under the Air Commerce Act, 1926-38” Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C.

Leaman, Paul. Fokker Aircraft of World War One. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire: Crowood Press, 2001.

Peck, Edward. “Ancestor Aircraft of TWA” Journal of American Aviation Historical Society; Fall, 1970.

Pigott, Peter. Brace for Impact: Air Crashes and Aviation Safety. Ottawa: Dundurn Publishing, 2016.

Pisano, Dominick A. “The Crash That Killed Knute Rockne,” Air & Space Magazine; December 1991/January 1992; Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.