What makes college football so special for so many is the sense of history and tradition that permeates the game – its rivalries, its pageantry, all the touchstones which keep its adherents coming back to campus year after year. No other sport, I would contend, retains such enduring loyalty and connection.

No matter how the 2020 college football season ultimately plays out, one thing is now certain: there will be no Notre Dame vs. Navy game for the first fall since the historic rivalry began in October of 1927.

The game has been played each year since then – 93 times. And in a sense, the series couldn’t help but prosper, as that first game matched the national champions of two of the previous three seasons – Notre Dame (1924) vs. Navy (1926). But even more than championship seasons and thrilling victories, the series is about profound respect between two institutions, and the molding of young lives that mark their traditions.

The game has been played each year since then – 93 times. And in a sense, the series couldn’t help but prosper, as that first game matched the national champions of two of the previous three seasons – Notre Dame (1924) vs. Navy (1926). But even more than championship seasons and thrilling victories, the series is about profound respect between two institutions, and the molding of young lives that mark their traditions.

By now, most fans of the two schools know the backstory of how the Navy essentially kept Notre Dame from closing during World War II, setting up an officers training program on the campus, thus keeping ND coffers full while most students were off fighting the war. In gratitude, Notre Dame promised the Naval Academy that it would always have a place on the Fighting Irish football schedule.

And that promise, in turn, is cited by the Middies football program when talking with prospects, especially those considering Army. In your four years as a Midshipman, you’ll face Notre Dame four times, twice at iconic Notre Dame Stadium.

Notre Dame’s history of high-profile inter-sectional games began under the tenure of athletic director and head coach Jesse Harper in 1913, when he was able to secure a date with mighty Army for Nov. 1. At West Point that day, a team led by quarterback Gus Dorais and end Knute Rockne utilized the forward pass as never before, using a series of long pass routes and arcing spirals to shock the Cadets, 35-13, in what’s been called “the game that changed football.”

The Notre Dame-Army series was born. In 1914, Harper added a trip to foundational leader Yale. And in 1915, a series with Plains power Nebraska began with a trip to Lincoln, and a 20-19 Husker victory that marred an otherwise perfect ND season.

The Nebraska series provided some classic battles over the next decade, but ultimately was ended by the Holy Cross fathers after a crudely anti-Catholic halftime show at Lincoln in 1925. Athletic director Rockne had wanted that series to continue, and now was in search of other options to keep “Rockne’s Ramblers” traveling about the country.

The trip to meet Leland Stanford University, its star Ernie Nevers and coach Pop Warner in the 1925 Rose Bowl had set the stage for a major rivalry which would return the Irish to the West Coach every other season. Matching Notre Dame with the University of Southern California was an immediate, huge success, with enormous crowds at the Los Angeles Coliseum and, before Notre Dame Stadium was built, the massive Soldier Field in Chicago.

The annual Army game had been relocated from West Point to New York City starting in 1923, and now was a staple at Yankee Stadium, and one of the East Coast’s major sporting events each year. Yet, Rockne saw value in giving the nation’s other military academy equal time.

From the Navy perspective, it was a prominent military family from southern Indiana that played a major role in the launch of the series.

In Jeffersonville, Ind., just across the Ohio River from Louisville, teenager Jonas Ingram (born in 1886, just 16 months before Rockne) left Jeffersonville High School to enter Culver Military Academy, from which he received an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy in 1903, at just 17 years of age.

Jonas Ingram became a successful athlete in Annapolis, and as a senior running back on Dec. 1, 1906, scored the only touchdown for the Midshipmen in their 10-0 victory over Army in Philadelphia, halting the Middies’ five-game winless streak against their arch-rival.

Ingram went on to a decorated military career, and in the Mexican campaign of 1914, he earned the Medal of Honor for his actions on April 22 with the Arkansas battalion, during the battle of Vera Cruz, Mexico. The citation hailed Ingram for “distinguished conduct in battle” and “skillful and efficient handling of the artillery and machine guns.”

The following year, Lt. Ingram was named head football coach for the Naval Academy, and guided the Middies in the 1915 and 1916 seasons. Among his players was his brother Bill Ingram, nearly 12 years his junior.

While brother Bill completed his final two years in Annapolis, Jonas Ingram returned to military action. During the Great War, Lt. Ingram served on the staff of Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman, a commander in the Atlantic Fleet, and was awarded the Navy Cross.

Jonas Ingram continued to rise through the Navy ranks, and in 1926, his services were again requested in Annapolis, where he became athletic director. Bill Ingram, meanwhile, had begun his own career in athletics, starting with a year as head coach at William & Mary (1922), before returning to his home state to guide the Indiana Hoosiers from 1923 to 1925.

One of Jonas Ingram’s first duties as Navy athletic director was to hire a head football coach to replace Jack Owsley, who led the Middies for just one season, 1925, before returning to his business career, where he was to become a leader in the armaments industry.

So Jonas Ingram turned to a former Navy football standout who was considered a rising star in the coaching game – his younger brother Bill. The pressure was on 28-year-old Bill Ingram to prove he belonged, and was not just the product of apparent nepotism.

Bill Ingram brought with him to Annapolis his first-year line coach from Bloomington in 1925, young Edgar “Rip” Miller. In the fall of 1924, Miller gained national recognition as a member of the Seven Mules – the line that played in front of the Four Horsemen of Notre Dame.

All 11 players were seniors at Notre Dame in 1924, sweeping to prominence in a 10-0 season that earned consensus National Championship honors. And in the fall of 1925, all 11 men were college football coaches, owing to their outstanding playing careers, and Rockne’s reputation and contacts across the nation. (Amazingly, three started as head coaches – Harry Stuhldreher at Villanova, Adam Walsh at Santa Clara, and Elmer Layden at Columbia in Iowa, today’s Loras University).

The Ingram brothers, as athletic director and coach, faced a challenging 1926 schedule, including games against Purdue and Michigan, and a trip to mighty Princeton. The Middies came through unscathed, winning nine straight games, including those vs. Purdue (17-13), Michigan (10-0) and Princeton (27-13). The victory over Michigan was the only game the Wolverines lost that season, and likely cost them national championship honors. It was the legendary Fielding Yost’s 25th and final year as head coach, and the team was led by the consensus All-American combo of quarterback Benny Friedman and end Bennie Oosterbaan.

What remained was the game considered by many to be the biggest ever played in college football up until that time. The annual meeting with Army was being played in the West for the first time, at Chicago’s mammoth Soldier Field. There, before a crowd exceeding 100,000, the teams battled to an epic 21-21 tie. The Middies finished 9-0-1 and won National Championship honors from several selectors.

There were now more colleges than ever hustling to get onto the Middies’ schedule, but none more prominent than Notre Dame. Both schools agreed that the game would merit a large, neutral-site stadium, so it was set for Oct. 15, 1927 at Baltimore Municipal Stadium. The Ingram brothers were delighted to battle their home-state power, and Rip Miller’s alma mater.

Coach Ingram’s 1927 squad opened with easy victories over Davis & Elkins (35-6) and Drake (27-0), while Rockne’s Irish dispatched Coe College (28-7), then traveled to Detroit and scored a 20-0 win over the U. of Detroit Titans, coached by Rockne’s old running mate, Gus Dorais.

A crowd of nearly 50,000 in Baltimore’s gleaming Municipal Stadium enjoyed the pomp and pageantry that surrounded this inaugural intersectional matchup. Rockne, as he did so often, employed the military strategy of starting his “shock troops,” an entire 11-man second unit, to start the game and take some of the energy out of Navy’s regulars. The Middies were successful in taking an early 6-0 margin, and led at halftime by that score. But now the rested Notre Dame regulars were in the game.

In the second half, Notre Dame’s relentless ground game, led by Christie Flanagan and John Neimic, proved largely unstoppable, and the Irish rolled to a 19-6 victory over the defending national champs. The series was off and running.

Bill Ingram coached the Middies another three seasons, before heading west in 1931 to take over the U. of California Golden Bears. His replacement at Annapolis was an easy choice – Rip Miller had already won countless friends at the Academy and beyond. The 30-year-old native of Canton, Ohio, guided the Middies the next three seasons, and in 1933 led them to their first victory over Notre Dame, 7-0 in Baltimore on Nov. 4.

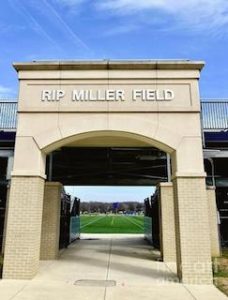

Miller stepped back into an assistant coaching role from 1934 to 1947, then served as an athletic administrator (essentially athletic director) at Annapolis from 1948 to 1974, In total, he was a prominent face of Navy athletics for nearly a half-century.

(And what became of Jonas Ingram? Well, in World War II, he was Commander-In Chief of the Atlantic Fleet and was personally responsible for the safety of the convoy of American troops to Europe, earning three Distinguished Service Medals and the Purple Heart.)

Fast forward to 2008, when plans were formulated to create a trophy honoring participants in the Notre Dame-Navy series; it was an easy choice to name it after the former ND “Mule” and long-time Navy figure, Rip Miller.

On Nov, 14 of that year, the day before yet another Navy-ND meeting in Baltimore, this time at Ravens Stadium, a luncheon was co-hosted at Camden Yards by the Notre Dame Club of Maryland and the Naval Academy Alumni Association, to announce plans for a Rip Miller Trophy.

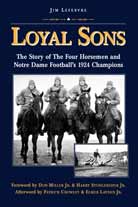

I was honored to be asked to speak on the life of Rip Miller at the luncheon. My first book, Loyal Sons: The Story of The Four Horsemen and Notre Dame Football’s 1924 Champions, had just been published that fall. In it, I tell the stories of all the key members of the 1924 national champions, including of course Rip Miller.

I wrote of how Miller had planned on attending Grove City College in Pennsylvania, until a chat with an ND alum steered him to South Bend, sight unseen. How he got to South Bend “riding the blinds,” occupying a cramped – but free – space behind the coal car. And later, on a blind double date with an Irish teammate, he met 16-year-old Esther Templin of Elkhart, who he would keep in touch with in the ensuing years, and eventually marry.

At that Baltimore luncheon in 2008, we arranged for Mrs. Esther Miller to be on hand – and we celebrated with Mrs. Miller her 102nd birthday, on that exact date. Vibrant and sharp, she lived another eight years, to 110.

Early in 2010, I was again asked to speak at a luncheon in Baltimore about Rip Miller, and Esther had the honor of unveiling the impressive Rip Miller Trophy.

Unlike most rivalry trophies, which are held each year by the winner of the game, the Rip Miller Trophy consists of two halves – honoring the captains of Navy and Notre Dame – which are re-assembled each year to honor the great shared history of this tremendous rivalry.

It’s a rivalry that must be resumed – if the world is ever going to approach looking normal again.