Notre Dame travels to Pittsburgh today for Saturday’s game against the Pitt Panthers. In recent years, the games have been decided by slim margins, regardless of the teams’ relative strengths. That’s consistent with a long history of close, dramatic contests, beginning more than a century ago.

On Oct. 30, 1909, Coach Frank “Shorty” Longman brought his ND gridders to play at Pitt, the furthest east Notre Dame had ever traveled for a football game up to that point. The South Bend visitors came away with a 6-0 victory, setting up an even bigger triumph the following Saturday – the historic 11-3 upset of Michigan at Ann Arbor, ND’s first-ever win against the team that taught it the game of football back in the 1880s.

The second trip to Pittsburgh came in 1911, with sophomores Gus Dorais and Knute Rockne starting to make their mark. Notre Dame had destroyed four lesser opponents by a combined score of 182-6, but the Panthers would be a totally different challenge. After the teams battled to a scoreless first half…

It was time for some trickery. For the start of the second half, (Ray) Eichenlaub executed a perfect onside kick and Rockne scooped up the ball and took off toward the Pitt goal line. Using his sprinter’s speed and the element of surprise, he raced into the clear. Notre Dame fans went wild with cheering as he crossed the Pitt goal line. For the first time, he had scored a touchdown for the varsity—in a crucial point of a hard-fought battle. One by one, his teammates joined him in the end zone to congratulate. But soon, confusion reigned. Referee F. D. Godcharles, a respected man from Lafayette College, waved his arms frantically. Notre Dame, he ruled, had begun the play before he formally opened the quarter with a whistle, and was technically offside. The ball was returned to midfield, with a penalty instead of a touchdown. The teams continued to slug it out without a score. Later, as if dictated by the conditions, a Pitt touchdown was also called back due to an offside call.

After the scoreless tie, the weary Notre Dame warriors were ‘feted and feasted’ by the school’s Pittsbugh alumni with ‘characteristic hospitality and good cheer.’ A Notre Dame writer noted that the whole experience served to “bind faster the chords of memory between us of today who are here (at ND) and those of yesterday who are in Pittsburgh.”

Notre Dame was learning the importance of playing games in distant locations. The Notre Dame family was putting down roots in cities and towns across the land.

The next season, 1912, Notre Dame again opened with four lopsided home victories against outmatched opponents before facing its major road test at Pittsburgh.

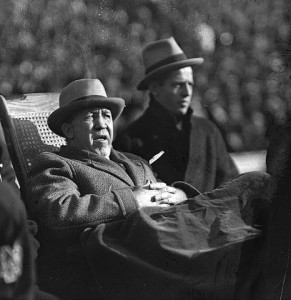

Knute Rockne in a wheelchair with player Frank Carrideo at practice when phlebitis sidelined the coach.

Notre Dame was determined to secure victory at Forbes Field this time. They didn’t count on the conditions that greeted them on Nov. 2: bone-chilling cold, biting wind, and snow. In these conditions, every yard was a battle; numerous fumbles and penalties kept both sides bottled up all day. Even when Rockne was able to break free for a gain of 33 yards on a perfect pass from Dorais in the third quarter, penalties derailed the drive and forced another punt. In the end, it was a 25-yard drop kick by Dorais that gave Notre Dame a hard-fought, 3-0 victory.

In three games at Pitt, Notre Dame had outscored the Panthers by a total count of 9-0. The two victories and one tie proved that ND was indeed ready to take on major opponents. But the Irish wouldn’t meet the Panthers again until 1930, Rockne’s final season as head coach. The 1920s would be marked by a series of trips to Pittsburgh to take on Carnegie Tech, which had a meteoric rise both in academic circles and football since its founding in 1900 by industrialist Andrew Carnegie. The Scots played a strong schedule, and under its coach, Judge Wally Steffen, was a formidable opponent. So strong that the Scots defeated Notre Dame twice – 19-0 in 1926 in Pittsburgh, and 27-7 in 1928, in the final game ever played at Cartier Field.

I

n the fall of 1929, there were a number of challenges for Notre Dame. The Irish were coming off a less-than-stellar 5-4 season; there were no home games scheduled, due to the construction of Notre Dame Stadium; and Rockne’s coaching was severely impacted by his health – a bad case of thrombophletibis, an inflammation of the veins in his legs. His mobility was limited, and he tried coaching from a prone position on a gurney. The Irish opened with wins over Indiana, Navy and Wisconsin, with Rockne giving his players instruction and encouragement by phone for the Navy game at Baltimore.

Doctors ordered continued bed rest and warned Rockne against excitement—or even activity—that might dislodge a blood clot from his legs and send it through his bloodstream, potentially causing a heart attack or stroke.

Rockne’s decision to bring (assistant coach Tom) Lieb back on the staff looked prescient. Every morning and every evening, Lieb came to the Rockne house and sat in the sickroom with the head coach, going over planning and personnel. Lieb then presided over the noon-time football talk and the afternoon practice.

Next up was Carnegie Tech, the team that always seemed poised to spoil Notre Dame’s season. It was only 11 months ago that Wally Steffen’s bunch embarrassed the Irish, 27-7, in their final game at Cartier Field. Carnegie had become a thorn in Rockne’s side that needed to be extricated. Rockne wanted this one—badly. Rockne ignored his doctors’ orders and was on the train with the team as they left for Pittsburgh. On Friday, he lay on a sofa in his room at the Pittsburgh Athletic Club, trading wisecracks and handing out tickets to his coterie of friends and admirers, including a number of newspapermen. In many ways, he was the old Rockne—jovial, witty, full of energy, the center of attention. Friday afternoon, he was wheeled to the gymnasium, where he oversaw the team’s drills. That evening, there was quiet in the vicinity of Rockne’s room. The coach was not entertaining visitors. It was so unlike the normal hustle and bustle of activity surrounding the night before a big game that rumors began to spread about his condition.

On game day, in the locker room at Forbes Field with 66,000 fans who packed every nook and cranny, Notre Dame’s players sat waiting, not sure whether Rockne had even survived the night. Suddenly, the door flung open, and Lieb strode in, carrying Rockne in his arms. He placed him on a table, where Rockne sat with his legs stretched out straight; he looked emotionless, serious, staring straight ahead and saying nothing, seemingly barely conscious of his surroundings. The players fidgeted in the nervous silence. Who was this man masquerading as their coach? They knew him as strong, fierce, animated, and emotional, and now he sat in their midst as an invalid. Was he there merely as a spectator? The moments passed, with the 2 p.m. kickoff now almost upon them. In a corner, team physician Dr. Maurice Kelly said to the man next to him, “If he lets go, and that clot dislodges, to his heart or his brain, he’s got an even chance of never leaving this dressing room alive.”

Then, as suddenly as a great gust of wind, the coach began to speak, clearly and forcefully. “A lot of water has gone under the bridge since I first came to Notre Dame, but I don’t know when I’ve ever wanted to win a game as badly as this one. I don’t care what happens after today. Why do you think I’m taking a chance like this? To see you lose?” His voice, rising now into a shout, went on. “They’ll be primed. They’ll be tough. They think they have your number. Are you going to let it happen again?” The room went quiet, as Rockne let his words penetrate the players’ souls. Then, like a great fighter making a final, valiant charge, he let loose, pouring every ounce of energy into his oration: “Go out there and crack ’em. Crack ’em. Crack ’em. Fight to live. Fight to win. Fight to live. Fight to win, win, WIN!” With a mighty roar, the players exploded from the room toward the field. Rockne collapsed, his eyes closed, his face sweating. The doctor attended to him, wiping his brow. It was no exaggeration to say Rockne had looked death in the face and survived. He wanted his boys to show similar courage—today on the football field, but also some other day, in some other place, when one would be summoned to perform against all odds.

As expected, Carnegie played Notre Dame tough in a fierce, physical battle. Rockne watched the proceedings from his wheelchair, calm now, efficiently grading the results and making adjustments. After a scoreless first half, he expected the Scots to pass; they did, and Notre Dame was ready. The biggest play came when Elder returned a punt to the Carnegie 7-yard line, and from there, the Irish fought their way to the game’s only score, a one-yard blast by Savoldi. With their 7-0 victory, the tired and battered Irish, and their ailing coach, made the return trip to South Bend in higher spirits.

The narrow victory helped propel the Irish onward toward a perfect season and consensus national championship. The next year, 1930, Notre Dame played both Pittsburgh schools on back-to-back Saturdays, downing Carnegie Tech, 21-6, in the third game ever played at Notre Dame Stadium, then traveling to defeat Pittsburgh, 35-19, before more than 66,000 at Forbes Field. That season would also finish with the Irish as undefeated national champions – with a well-established tradition of pivotal games held in Pittsburgh.

Portions of the preceding are excerpted from Coach For A Nation: The Life and Times of Knute Rockne (2013, Great Day Press) by Jim Lefebvre. All rights reserved.